We started looking at databases using the Py4E text and creating databases in Python. To understand how to work with databases in Python, I think it is a bit easier to start working with databases directly. Then we can think about how to get python to tell the database what we want, since we already have a better idea of what databases can do and how to do things with SQL.

For this exercise we will use the world database from MySQL.

Setup the world.sqlite database:

For this section, we will work with a “canned” database. This one is distributed by the developers of MySQL and is called “world”.

I have done some converting so that it is ready to work with sqlite. The database is in the Class_files git repo and on the cluster at: /blue/bsc4452/share/Class_Files/data/world.sqlite.

There are three tables:

- cities: containing information on cities around the world.

- countries: containing a bunch of countries and information about them.

- countrylanguage: containing the languages spoken in each country.

Copy the database and open sqlite

Make a copy of the database and open it in sqlite. Do not try to use the copy in /blue/bsc4452/share/Class_Files–you want a copy that you can modify. So, either use your own clone of the repo or make a copy of the file in your own directory on the cluster.

[magitz@login4 db]$ module load sqlite

[magitz@login4 db]$ sqlite3 world.sqlite

SQLite version 3.8.8.2 2015-01-30 14:30:45

Enter ".help" for instructions

Enter SQL statements terminated with a ";"

sqlite>

This gets us to the sqlite command prompt–similar in appearance to the Python command prompt. Since we gave sqlite the name of the database we wanted to use on the command line, it’s already open. If we hadn’t done that, we can use .open world.sqlite.

sqlite vs. the world!

Note that in most DBMS, the command would be use world; or whatever the name of the database is–another “uniqueness” with sqlite…

One of the things I don’t really like about sqlite is that it uses some non-conventional commands compared to most other relational databases. Many of these are easy to figure out, but still a bit of a pain. This page is a decent review of the commands: https://www.sqlite.org/cli.html

There are also some other non-standard things, like the type “feature”. I’ll do my best to find and point those out to you as well as point out standard SQL conventions/commands even if sqlite doesn’t use them. Hopefully this will help with Googling answers…

Verify that the database is loaded

In sqlite the .database command shows the current database (MySQL: SHOW DATABASES; displays the databases, USE DATABASE name; makes that one the active database).

sqlite> .database

seq name file

--- --------------- ----------------------------------------------------------

0 main /blue/bsc4452/share/magitz/world.sqlite

sqlite>

Explore the tables

See what tables are in the database: .tables (MySQL:``SHOW TABLES;`)

sqlite> .tables

city country countrylanguage

sqlite>

See the information about a table .schema city (MySQL: DESCRIBE city;)

sqlite> .schema city

CREATE TABLE `city` (

`ID` integer NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT

, `Name` CHAR(35) NOT NULL DEFAULT ''

, `CountryCode` CHAR(3) NOT NULL DEFAULT ''

, `District` CHAR(20) NOT NULL DEFAULT ''

, `Population` integer NOT NULL DEFAULT '0'

, CONSTRAINT `city_ibfk_1` FOREIGN KEY (`CountryCode`) REFERENCES `country` (`Code`)

);

Unlike the DESCRIBE command of most database systems, which shows a table with the column names and properties, like the data type and key information, the .schema command of sqlite shows the command that was used to create the table. Basically the same information, but a different format.

Let’s look at this line-by-line:

CREATE TABLE `city` (

This is the SQL line saying that we want to create a table called city.

`ID` integer NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT

The first column is:

- called ID,

- it is an integer,

- it cannot be empty (NOT NULL),

- is a primary key,

- and it auto-increments, meaning that, as each new row of data is added, the database system automatically assigns the next highest integer for this record.

The ID column is the Primary key. Primary keys are guaranteed to be unique and present for each row. Generally, we let the database system manage these–don’t try to assign your our values to the ID unless you have a really good reason to do so.

, `Name` CHAR(35) NOT NULL DEFAULT ''

, `CountryCode` CHAR(3) NOT NULL DEFAULT ''

, `District` CHAR(20) NOT NULL DEFAULT ''

, `Population` integer NOT NULL DEFAULT '0'

These lines aren’t the most exciting, they are just adding some more columns to our table, Name, CountryCode, District and Population. Note that since this originally came from a MySQL database, there are some very specific data types (e.g. CHAR(3) means that CountryCode can be at most 3 characters long). sqlite will accept this, but then happily allow you to put whatever data you want in that column…

, CONSTRAINT `city_ibfk_1` FOREIGN KEY (`CountryCode`) REFERENCES `country` (`Code`)

The CountryCode in the city table we are making here will reference a column in another table. This line sets this up by adding a CONSTRAINT named ‘city_ibfk_1’ (don’t worry about the constraint name–ibfk is short for innodb foreign key: just a naming convention). The constraint says that the CountryCode column in the city table is a FOREIGN KEY that REFERENCES the Code column in the country table.

That means that anything entered into the CountryCode column in the city table has to match a record in the Code column of the country table. Let’s see what happens if we try to enter a line with a code that doesn’t exist.

Non-Standard sqlite “feature” alert: Unless you tell sqlite to turn on enforcing foreign key constraints, it doesn’t do it by default!

So, we’ll set foreign_keys=ON and then try to insert a row into the city table, using XXX for the country code (a code not in the country table):

sqlite> PRAGMA foreign_keys = ON;

sqlite> INSERT INTO `city` VALUES (1234567,'Amsterdam','XXX','Noord-Holland',731200);

Error: FOREIGN KEY constraint failed

sqlite>

This INSERT fails because the country code XXX fails the constraint that we put on it.

Let’s move to the countrylanguage table

In the countrylangue table, we see that both CountryCode and Language are primary keys–use .schema countrylanguage , PRIMARY KEY (CountryCode,Language). This is what is called a composite key, and it takes both columns to ensure uniqueness. This is an example of a many-to-many relationship. Some countries have more than one language and languages are spoken in many countries. Neither country nor language are, on their own unique, but in combination, they are. Many-to-many tables often use composite keys. Again the CountryCode is constrained and defined as referencing back to Code in the country table.

Look at the data

SELECT, WHERE and LIMIT

A SELECT statement is used to get data from a table.

Run: SELECT Id, Name, Population FROM city; That generates a long list of output the runs off the top of the screen and isn’t terribly nicely formatted.

Luckily, sqlite’s “dot” commands can make the output formatting a bit nicer if you want, Plus we can add the LIMIT 10 command to limit the output to the 1st 10 entries.

sqlite> .mode column

sqlite> .headers on

sqlite> SELECT Id, Name, Population FROM city LIMIT 10;

ID Name Population

---------- ---------- ----------

1 Kabul 1780000

2 Qandahar 237500

3 Herat 186800

4 Mazar-e-Sh 127800

6 Rotterdam 593321

7 Haag 440900

8 Utrecht 234323

9 Eindhoven 201843

10 Tilburg 193238

11 Groningen 172701

Adding in WHERE, we get only the data where some condition is met:

sqlite> SELECT Id, Name, Population FROM city WHERE Population > 5000000;

ID Name Population

---------- ----------- ----------

206 S�o Paulo 9968485

207 Rio de Jane 5598953

456 London 7285000

608 Cairo 6789479

939 Jakarta 9604900

1024 Mumbai (Bom 10500000

1025 Delhi 7206704

1380 Teheran 6758845

1532 Tokyo 7980230

1890 Shanghai 9696300

1891 Peking 7472000

1892 Chongqing 6351600

1893 Tianjin 5286800

2257 Santaf� d 6260862

2298 Kinshasa 5064000

2331 Seoul 9981619

2515 Ciudad de M 8591309

2822 Karachi 9269265

2823 Lahore 5063499

2890 Lima 6464693

3320 Bangkok 6320174

3357 Istanbul 8787958

3580 Moscow 8389200

3793 New York 8008278

sqlite>

Returns the cities with a population over 5,000,000.

ORDER BY

To sort the above list, we can add the ORDER BY command:

sqlite> SELECT Id, Name, Population FROM city WHERE Population > 5000000 ORDER BY Population DESC LIMIT 10;

ID Name Population

---------- --------------- ----------

1024 Mumbai (Bombay) 10500000

2331 Seoul 9981619

206 S�o Paulo 9968485

1890 Shanghai 9696300

939 Jakarta 9604900

2822 Karachi 9269265

3357 Istanbul 8787958

2515 Ciudad de M�x 8591309

3580 Moscow 8389200

3793 New York 8008278

sqlite>

And, if we want to see the next 10:

sqlite> SELECT Id, Name, Population FROM city WHERE Population > 5000000 ORDER BY Population DESC LIMIT 10, 11;

ID Name Population

---------- ---------- ----------

1532 Tokyo 7980230

1891 Peking 7472000

456 London 7285000

1025 Delhi 7206704

608 Cairo 6789479

1380 Teheran 6758845

2890 Lima 6464693

1892 Chongqing 6351600

3320 Bangkok 6320174

2257 Santaf� 6260862

207 Rio de Jan 5598953

sqlite>

Summarize with COUNT()

We may want to summarize the information. How many cities to we have data for? COUNT(*) counts the rows returned–we are using SELECT * here since we don’t really care what columns we get back–we won’t see them anyway..

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM city;

COUNT(*)

----------

4078

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM country;

COUNT(*)

----------

239

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM countrylanguage;

COUNT(*)

----------

984

sqlite>

We can also combine COUNT() with WHERE:

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM countrylanguage WHERE language = "English";

COUNT(*)

----------

60

sqlite> SELECT COUNT(*) FROM city WHERE Population >5000000;

COUNT(*)

----------

24

sqlite>

Summarize data with MIN() and MAX()

sqlite> SELECT Name, Population FROM city WHERE Population = (SELECT MAX(Population) FROM city);

Name Population

--------------- ----------

Mumbai (Bombay) 10500000

sqlite> SELECT Name, Population FROM city WHERE Population = (SELECT MIN(Population) FROM city);

Name Population

---------- ----------

Adamstown 42

sqlite>

LIKE

In addition to the normal =, >, =, etc, for text matches, there’s a LIKE match that offers wildcard searches, but not quite regular expressions. So for example:

sqlite> SELECT Name, District, Population FROM city WHERE Name LIKE 'Gain%';

Name District Population

----------- ---------- ----------

Gainesville Florida 92291

sqlite> SELECT Name, District, Population FROM city WHERE Name LIKE 'New %';

Name District Population

---------- ----------- ----------

New Bombay Maharashtra 307297

New Delhi Delhi 301297

New York New York 8008278

New Orlean Louisiana 484674

New Haven Connecticut 123626

New Bedfor Massachuset 94780

sqlite>

GROUP BY

The GROUP BY command can be used to combine things by group–often to summarize data.

So if we want to know the sum of the populations of the cities in Florida, we can do:

sqlite> SELECT District, sum(Population) FROM city WHERE District='Florida' GROUP BY District;

District sum(Population)

---------- ---------------

Florida 3151408

sqlite>

HAVING

With grouped data, instead of WHERE, we can use HAVING. So to find states with populations over 3 million, we can do:

sqlite> SELECT District, SUM(Population) FROM city where CountryCode='USA' GROUP BY District HAVING SUM(Population) > 3000000;

District SUM(Population)

---------- ---------------

Arizona 3178903

California 16716706

Florida 3151408

Illinois 3737498

New York 8958085

Texas 9208281

sqlite>

Joining tables

JOIN commands are where databases shine! This is what gives you the ability to combine data from different tables as you make your queries. The idea of a JOIN is to take data from two or more tables, using the common information in those tables.

So, in the example, we are taking the Name from the country table and the Language and Percentage from the countrylanguage table, and joining them using the Code column of the country table and the CountryCode column of the countrylanguage table. Here’s the query:

sqlite> select Name,Language,Percentage FROM country JOIN countrylanguage ON Code=CountryCode WHERE Language='Portuguese' ORDER BY Percentage DESC;

Name Language Percentage

---------- ---------- ----------

Portugal Portuguese 99.0

Brazil Portuguese 97.5

Luxembourg Portuguese 13.0

Andorra Portuguese 10.8

Guinea-Bis Portuguese 8.1

Paraguay Portuguese 3.2

Macao Portuguese 2.3

France Portuguese 1.2

Canada Portuguese 0.7

United Sta Portuguese 0.2

Cape Verde Portuguese 0.0

East Timor Portuguese 0.0

sqlite>

Here’s another example from this page:

sqlite> SELECT C.Name AS Country, MAX(T.Population) AS N FROM country C LEFT JOIN city T ON C.Code = T.CountryCode GROUP BY C.Name ORDER BY N DESC ;

Country N

---------- ----------

India 10500000

South Kore 9981619

Brazil 9968485

China 9696300

Indonesia 9604900

Pakistan 9269265

Turkey 8787958

Mexico 8591309

Russian Fe 8389200

United Sta 8008278

Japan 7980230

United Kin 7285000

...<snip>...

There’s a fair bit new in this example. First off, they are using the as renaming, as well as aliasing. Kind of like in Python where we import pandas as pd, we can do similar things in SQL. The example also aliases table names; here’s a simpler example (also from the above page):

sqlite> SELECT C.Name FROM country C, countrylanguage L WHERE C.Code = L.CountryCode AND L.Language = 'Greek';

Name

----------

Albania

Australia

Cyprus

Germany

Greece

sqlite>

So we say, SELECT C.Name (oddly before C is defined, but such is SQL!) and then in the FROM, we say country C, which tells sqlite that we are referring to the country table as C. Similarly, the code uses L for the countrylanguage table–sure a lot easier to type out when you use it multiple times in query.

So, returning to the join above…Not only do we alias tables, country C and city T, we also use the AS to rename column headers in the output, so rather than print Name as the header, it prints Country, since we did C.Name AS Country and rather than Population, we get N (from MAX(T.Population) AS N).

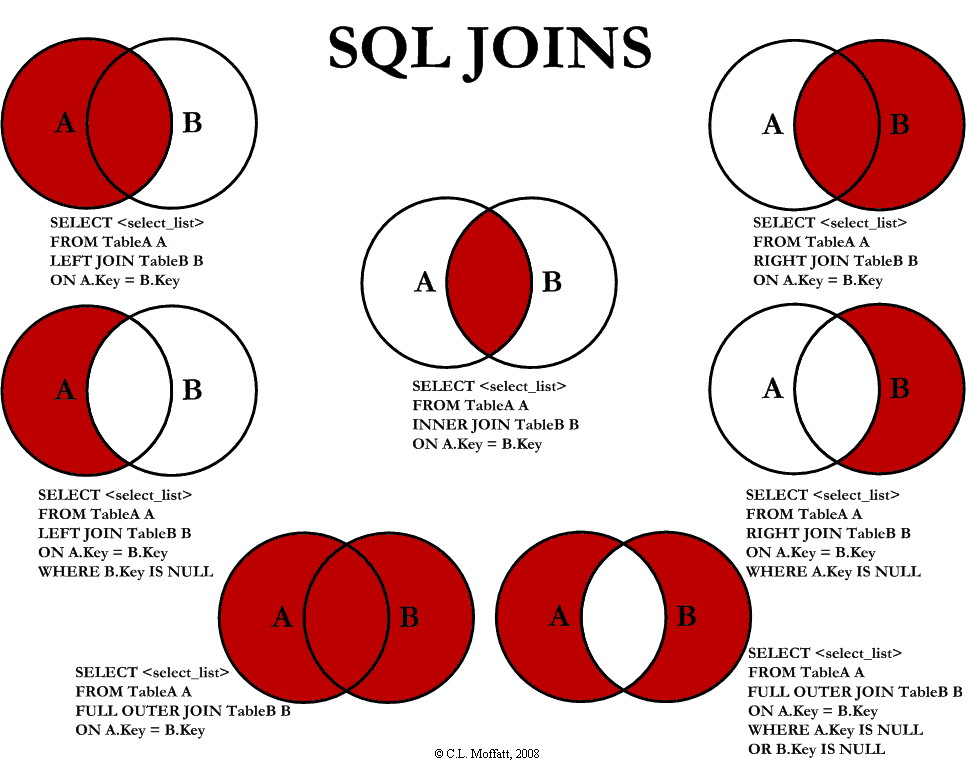

Now the type of JOIN here is a LEFT JOIN. There’s a good tutorial on JOINs on this page but here’s the summary picture:

So, a LEFT JOIN on two tables is the top left diagram, where you get all of the rows in A and if a corresponding row doesn’t exist in B, the result is filled with NULLs.

In our case, we get all of the countries, and if there are no cities in that country, we still get the country name, but a null value for the largest city in the country.

An INNER JOIN would give us basically the same information, but leave off the several rows at the end that don’t have cities.

Let’s try another JOIN. Where is Portuguese spoken and in what percentage of the population?

sqlite> select Name,Language,Percentage FROM country JOIN countrylanguage ON Code=CountryCode WHERE Language='Portuguese';

Andorra|Portuguese|10.8

Brazil|Portuguese|97.5

Canada|Portuguese|0.7

Cape Verde|Portuguese|0.0

France|Portuguese|1.2

Guinea-Bissau|Portuguese|8.1

Luxembourg|Portuguese|13.0

Macao|Portuguese|2.3

Portugal|Portuguese|99.0

Paraguay|Portuguese|3.2

East Timor|Portuguese|0.0

United States|Portuguese|0.2

Unfortunately, because of how the keys are setup on this and all country codes are in all tables, I can’t think of good outer join examples for these data…

But you can keep playing with JOIN and other queries…

Modify the date with UPDATE

Now that we’ve done some exploring of data, let’s look at changing data in a database. Who is the president?

sqlite> SELECT Name, HeadOfState FROM country WHERE Name = 'United States';

Name HeadOfState

------------- --------------

United States George W. Bush

sqlite>

Hmm… this database is a bit out of date. Let’s update that information.

sqlite> UPDATE country SET HeadOfState = 'Donald Trump' WHERE Name = 'United States';

sqlite> SELECT Name, HeadOfState FROM country WHERE Name = 'United States';

Name HeadOfState

------------- ------------

United States Donald Trump

sqlite>